The North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh has an exceptional exhibit covering cars of the Art Deco period, and the show closes on Sunday, January 15, 2017, so this would seem to be a good moment to hit the highlights. The show encompasses cars built in the 1930s and 1940s, and while the curators have identified the prevailing style as Art Deco, there are also examples of Streamline Moderne, as well as a style Raymond Loewy long ago christened "Borax." We'll get to that in a moment. First, some distinctive faces which may be familiar to longtime readers of poeschloncars...

Photo Credit: All photos but two are by longtime reader George Havelka, who reports that the Xenia's paint job is a knockout for depth and luminosity. The detail of the Scarab hood ornament is from the website aerodynamicsproject.com, and the rear view is from remarkablecars.com.

This spectacular 1938 Xenia, built for aperitif king and inventor Andre Dubonnet on an Hispano Suiza chassis by Saoutchik to a design by Jean Andreau, was covered in detail in our essay "One of One, a Brief History of Singular Cars" from September 7, 2015. Among its innovations: sliding doors, compound curved windshield and curved side glazing, and teardrop fenders which (at the rear anyway) flow out of the body sides before merging into the tapered tail.

The Tatra T87 from 1936 to 1950 was the product of Czech engineer Hans Ledwinka, and featured a rear-mounted, air-cooled overhead cam V8, along with aerodynamic bodywork along lines pioneered by Paul Jaray. The triple headlights, 3-piece wraparound windshield, flush sides and single dorsal fin were very advanced, and betray a confident (and misplaced, for Central Europe in 1936) faith in the ability of technology to solve all problems. The car, along with Ledwinka's rivalry with Porsche and lawsuit against VW for patent infringement, is covered in our essay "Cars and Ethics: A Word or Two on VW" in the archives from November 27, 2015.

This Delahaye Type 135M* which was bodied by Figoni & Falaschi with spatted wheels in a style inspired by cartoonist Geo Ham seemed, like the Xenia, designed for a jet set that would have to wait awhile for those jets. Like the Tatra, the exuberance and confidence of the design reminds us of cartoons of a lost future by artists like Bruce McCall. But that's with the benefit of hindsight. The Delahaye, with its outdated mechanical brakes and pushrod engine, was a poem about the future, while the Tatra, with its alloy engine and overhead cams, was an attempt at a blueprint for it…

The1930 Ruxton is early Deco, with a horizontal striped, very American multicolor paint job attempting to distract us from the very upright, un-aerodynamic bodywork. Streamline Moderne it's not.

The 1936 Peugeot 402 Darl'mat, designed by Georges Paulin for the coach builder Pourtout, has more of a kinship with the Delahaye. The two-toning and portholes in graduated sizes lend the design a whimsical air; the metal roof is practical, and Pourtout pioneered the retractable metal roof on the 402.

Over in the States, at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair, designer Phil Wright attempted to pull the conservative Pierce Arrow firm into the future with the SIlver Arrow V12, and deleted running boards for flush sides, integrating tubular headlight nacelles and teardrop rear fenders into a budget-busting composition that found only a handful of Depression buyers.

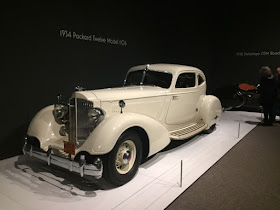

A car similar to the Packard V12 Model 1106 coupe was also shown at the Fair. Unlike the Silver Arrow, it has separate fender forms. But the teardrop form of those fenders, echoed in the side window shape, is in the spirit of the times.

Jean Bugatti tried to predict the future for Bugatti with his 1935 Aerolithe; this green phantom is a faithful replica on a Type 57 Bugatti chassis from the period. The original was lost, as Bugatti's future in Alsace Lorraine involved a German occupation, and no customers for magnesium-bodied twin cam dream cars.

William Stout tried, like Ledwinka at Tatra, a rear-mounted V8 (here, a Ford) format to maximize interior space. The Stout Scarab anticipated minivans in its efficient, cavernous interior. But the application of Egyptian themes, overlapping wing motifs, and the bathtub approach to streamlining echoes its own times (the first alloy-bodied Scarab was built in 1932; later cars were steel) and anticipates the next decade. The unconscious humor of the design shows a naive faith in streamlining that Raymond Loewy labeled "Borax". Perhaps he thought of this as the style was supposed to be clean, and Borax was a cleaning product... Only a few Scarabs were built at $5,000 a copy; five survive.

The 1941 Chrysler Thunderbolt is firmly in the late Streamline Moderne period, with its alloy envelope body designed by Alex Tremulis (later the designer of the Tucker), its fully enclosed wheels, and its retractable metal roof following Georges Paulin's innovations at Pourtout and Peugeot. Six cars were built as "cars of the future", but there was a war in America's future instead. After that war, a Thunderbolt appeared in the TV series "Boston Blackie."

*The Delahaye's brief moment of heroic achievement was covered in our essay "Dreyfus and the Million-Franc Delahaye vs. the Third Reich", on Nov. 22, 2015.

Happy New Year to all our readers, and thanks for your over 23,000 visits. We look forward to reporting on new and old Roadside Attractions in 2017, along with features on the Frazer Nash, the cars of Briggs Cunningham, and some cars we hope will be completely new to you...