When privateer Arthur Duray entered chocolatier Jacques Menier's 90 hp car in the 500 for 1914, he was not taken seriously by other drivers. After all, the Peugeot factory's entry consisted of 5.6 liter cars, and Delage had entered its 105 hp GP cars. The other drivers called Duray's mount "the baby"…until he broke the Indy lap record at 99.85 mph. Imagine, for a moment, averaging almost 100 mph on the narrow tires available back then, and on a track known as the Brickyard for a reason. In the race itself, Duray led for a few laps, but averse to damaging his friend Menier's baby, was content to finish second behind a Delage...

That second-place finish was considered a triumph of small, high-output engines over lumbering trucks, and by the Twenties all engines raced at Indy reflected the influence of engineer Ernest Henry's design for Peugeot. His inline four featured double overhead camshafts, four valves per cylinder, and made half a horsepower per cubic inch; it was only 6 cubic inches bigger than a Ford Model T. The exposed valve springs were soon to disappear from Henry's designs. The Peugeot on display at the Revs Institute is the actual car that Duray drove to humble most of the field at Indy...

Duray's countrymen at Delage* were among the first to learn these lessons. Designer Albert Lory's 1926 GP engine had half the displacement of the Peugeot, at 1.5 liters. While it shared the twin overhead cam configuration, its eight cylinders had two valves each, and the Roots-type supercharger allowed 170 horsepower at a shocking 8,000 rpm, or nearly 2 hp per cubic inch... For 1927, the model year shown, Lory redesigned the engine to reverse intake and exhaust manifolds, and thus to move the hot exhaust pipe away from the driver, who needed to stay on the right for the clockwise tracks. This was Lory's masterpiece, and race results were good enough that Louis Delage retired his firm from racing after that year. How good were the results? Robert Benoist won every race he entered, becoming the first world champion driver ever...

In 1915, a racer came to Los Angeles carburetor builder Harry Miller with a broken Peugeot racing engine like the one from the previous year's Indy 500. Unable to source parts from a war-ravaged France, he asked Miller to rebuild it. Miller effectively made a new Peugeot engine, and incorporated the Peugeot's key features into his own subsequent racing engines, including twin overhead cams and four valves per cylinder. Miller built both 4 and 8 cylinder engines, including the inline 122 cubic inch four that powered a Duesenberg to victory in the 1922 Indy 500. Between 1922 and 1938, Miller engines powered cars to 12 victories at Indy, half of them in chassis also built by Miller. The Miller designs became the basis for the Offenhauser engines that dominated Indy, and in smaller 110 cubic inch size, midget car racing, for decades.

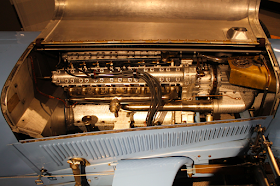

At his workshops in Molsheim, Alsace Lorraine, Ettore Bugatti answered the twin-cam designs of Delage and Miller by issuing the Type 51 in 1931; it was essentially a twin-cam version of his famous 2.3 liter Type 35 inline eight, supercharged and now with 160 hp. The road-going Type 55 below dates from 1933 and has a version of the T51 engine expanded to nearly 3 liters. Supercharged and with 2 valves per cylinder, the T55 made 135 hp at 5,500 rpm.

Art historians have suggested that the shear, sharp-edged rectangular masses and pure cylindrical shapes on Bugatti engines were inspired by Cubism, but based upon the recollections of those who worked in, or visited, the Molsheim factory in the 1930s, a more likely explanation for these pure geometric solids could be the limitations imposed by Bugatti's machine tools. Whatever the reason, the purity of form, and details like the hand-tooled pattern on the cam covers, will always be associated with Bugatti, and with high performance engines.

One of Bugatti's chief competitors, Alfa Romeo began producing a road-going version of its GP car, VIttorio Jano's 8C2900, in 1936. Alfa entered 3 cars in the 1936 Mille Miglia, and they finished in 1-2-3 order. By 1938, the 8C32900B was developing 180 hp at 5,200 rpm from the twin-cam, supercharged inline eight with 2 valves per cylinder. The alloy blocks were cast in unit with the heads, and two four-cylinder units were separated by the central gear tower which drove the cams. As with the Bugatti, the Alfa designs of this period had a visual harmony and dedication to detail that created a performance image for their maker.

One of Bugatti's chief competitors, Alfa Romeo began producing a road-going version of its GP car, VIttorio Jano's 8C2900, in 1936. Alfa entered 3 cars in the 1936 Mille Miglia, and they finished in 1-2-3 order. By 1938, the 8C32900B was developing 180 hp at 5,200 rpm from the twin-cam, supercharged inline eight with 2 valves per cylinder. The alloy blocks were cast in unit with the heads, and two four-cylinder units were separated by the central gear tower which drove the cams. As with the Bugatti, the Alfa designs of this period had a visual harmony and dedication to detail that created a performance image for their maker.

The 3 liter, supercharged DOHC V-12 of the 1939 Mercedes-Benz W154 (Chassis 15, the last) reflects the cost-no-object racing juggernaut of the German government-supported teams, both Mercedes and Auto Union. This car won the Belgrade Grand Prix on the day that another juggernaut, the Nazi army, invaded Poland. The engine on this car is always exposed, as the bodywork has been cut away on one side to display the chassis. The forms and details of the engine and related plumbing betray none of the regard for visual artistry shown in the Bugatti and Alfa; they are, instead, a workmanlike assemblage of elements in constant need of attention from a flotilla of factory-trained mechanics in order to perform as designed. An example of this approach is the rearward tilt of the engine block...

When American Don Lee entered a W154 in the 1947 Indy 500 (photo below), mechanics left the engine idling for a long warm-up during practice, and due to this tilt, fuel collected in the cylinders at the rear, resulting in broken connecting rods and a broken piston. Enterprising machinists fabricated a new piston and rods from drawings which were (amazingly) on hand, but the piston failed again in the race, with Duke Nalon at the wheel. In a reversal of the old Subaru slogan, it appears the W154 was designed to be expensive…and to stay that way.

This completes our review of racing engines during the Classic Era. In the next installment we'll have a look at the innovations, and repetitions, of the postwar era.

Photo Credits: All photos were provided by Paul Anderson, except for the Mercedes W154 (by the author), the W154 at Indy (wikimedia) and the Alfa 8C2900B (the Revs Institute Collier Collection.).

No comments:

Post a Comment