This year's third Chicago Architecture Biennial, which closes January 5, was destined from its inception to be more than a survey of form and style. Other shows have offered ideas for visitors interested in renovating their houses; this one was more about renovating our society. Entitling the show "…And Other Such Stories", artistic director Yesomi Umolu invited an international array of participants to explore 4 themes. These were "No Land Beyond", focusing on landscape and ecological context, "Appearances and Erasures", addressing histories, memory and monuments, "Rights and Reclamations" relating to activism by archiitects and planners, and finally "Common Ground." The Chicago Cultural Center on Michigan Avenue offered 70,000 square feet of exhibits as a starting point for exploring related events all around the city. The first exhibit that greets the visitor is housed in four humble, gable-roofed glass houses designed by MASS Design Group and artist Hank Willis Thomas*. Entitled the Gun Violence Memorial Project, it is what it claims to be...

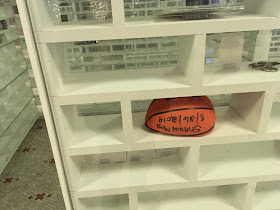

Each house represents an average week's toll of gun fatalities in the United States (about 700 people); taken together, the four glass houses represent a month's toll. Brick-shaped spaces lining the outer walls permit display of personal effects of victims, including cameras, jewelry, stuffed animals and toys..

Interviews conducted with victim's families are projected on screens above the displays. I stopped for a long moment to consider the inscription above the toy truck shown on the shelf below: "Arthur Kenneth Jones: 1997-2007"...

An installation prepared by FICA, a Brazilian non-profit devoted to affordable housing in Sao Paulo, allows the visitor to walk through a life-size space of one of their renovated apartments; the floor plan, including bath, kitchen appliances and furniture, is etched (logically enough) on the floor. Videos show interviews with the apartment's occupants, who express satisfaction at finding modern, affordable housing in the city. The revelation for the visitor is that the happy parents are raising 3 small children in a space of only 570 square feet, about the size of an American studio apartment...

Another exhibit expands on passive solar ideas pioneered by Steve Baer of Zomeworks in the 1970s. The faceted plywood modules could be quickly erected to provide nearly instant, solar-heated housing in emergencies, or in the context of the "long emergency" presented by persistent homelessness in nearly all our urban areas...

The Anthony Overton Elementary School, designed by Perkins & Will in 1963 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2016, was the subject of a controversial closure in 2013, and is now the subject of collaborative studies by studioBASAR, Borderless Studio, and Zorka Wollny, among others, as it begins the transition to an enterpreneurship center for Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood. The renovation of this important structure may provide a critical community gathering space and business incubator in an underserved, neglected neighborhood. The building's generous expanse of window walls reflects the International Style, while the broad horizontals of the eaves provide a link to Wright's work, and in the photo below, a precarious perch for gathered students, who are perhaps wondering what comes next...

Biennial events are scheduled all over the city, and include films, lectures and even musical and dance presentations. The events extend into the suburbs, and this year the Elmhurst Art Museum opened its renovated McCormick House, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1952, to the public. Designed for developer Robert McCormick III, who had worked with Mies on the 860 and 880 Lake Shore Drive high-rise apartments, it was intended as a prototype for affordable, manufactured modular housing…

Biennial events are scheduled all over the city, and include films, lectures and even musical and dance presentations. The events extend into the suburbs, and this year the Elmhurst Art Museum opened its renovated McCormick House, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1952, to the public. Designed for developer Robert McCormick III, who had worked with Mies on the 860 and 880 Lake Shore Drive high-rise apartments, it was intended as a prototype for affordable, manufactured modular housing…

The plan displaces two similarly-sized rectilinear blocks around a carport with the entry foyer at the intersection. This allows for a utilitarian wing with kitchen, utility room and children's rooms, as well as a wing with living room, master bedroom and study.

Steel framing allowed floor-to-ceiling permiteter glazing with the same window units and vertical steel I-sections as at the Lake Shore Drive buildings, but here the steel was painted white instead of black, and the blank end walls were brick.

McCormick partnered with Herbert Greenwald to build this first house as a model to attract buyers for the modular housing scheme, but not enough advance orders were placed to fund the project. McCormick moved into the house with his wife Isabella Gardner, who wrote two books while living there. In 1961 the house was rented to a family with six children, providing a test of its real-world livability. In 1963, Ray and Mary Ann Fick bought the house and raised their two sons there, staying nearly 3 decades...

Among the challenges of living in a mostly-glass house were keeping the rooms cool in summer (long expanses of glazing faced west) and warm in winter (glazing was not the insulated variety). There was also the issue of screening off the private spaces from public exposure, but over the decades Mother Nature took care of that...

By the 1980s, the lush growth of trees and foliage lent the McCormick House two attributes Mies had neglected to provide: shade and privacy. The Fick family sold the house to the Elmhurst Fine Arts & Civic Center Foundation in 1991, and the Foundation moved the house to the campus for their future museum in 1994. It was joined on site by the new Elmhurst Art Museum in 1997.

Among the changes resulting from the move was reorienting the west elevation to the south, and reconfiguring the interior for use by the Foundation and Museum stalff as office and conference spaces. Initially the house was connected to the museum by an enclosed passageway, but this has been removed in the most recent renovation to expose the original carport.

Mies liked to say that "God is in the details", but he avoided some kinds of details because they were hard to reconcile with his spare, stripped-down minimalism. One example is the complete lack of gutters and downspouts on a flat-roofed building…in Illinois, where rain and snow are plentiful. Instead, the photo above shows some odd plumbing directing water from the roof downward to the ground plane.

The interior spaces, though, reflect the openness and lightness that were supposed to suit the open minds and egalitarian attitudes of the postwar era. In the latest renovation, the bedrooms and living room have been refurnished in a style fitting the original, using some pieces designed by Mies and by Lilly Reich.

The Art Msueum's plan is to rebuild the kitchen and baths to match the original, so that the house will return to the original configuration of the modular prototype as proposed by Mies and McCormick. On the day I visited the McCormick House, I was alone in it the whole time. Perhaps society is no more ready today for a transparent, modular house than it was in 1952. Or maybe even getting the details right will not satisfy the consumer unless the details are part of a compelling and, equally important, affordable scheme. God may indeed be in the details, but if we don't come up with a coherent design for living as a context for those details, our buildings and our cities will fall short of their potential.

*Footnote: Other participants on the memorial project included the Chicago advocacy group Purpose Over Pain, and Everytown for Gun Safety, a national non-profit focusing on gun violence.

Photo Credits:

Photo Credits:

Top 3 + 5th from top: the author

4th + 6th: archdaily.com

3rd + 4th: squadrataraschi.it

7th: Michael Dant, reproduced at miessociety.org

8th: Elmhurst Museum of Art

9th: Hedrich Blessing Archives

10th + 11th: Elmhurst Museum of Art

12th to bottom: the author

No comments:

Post a Comment