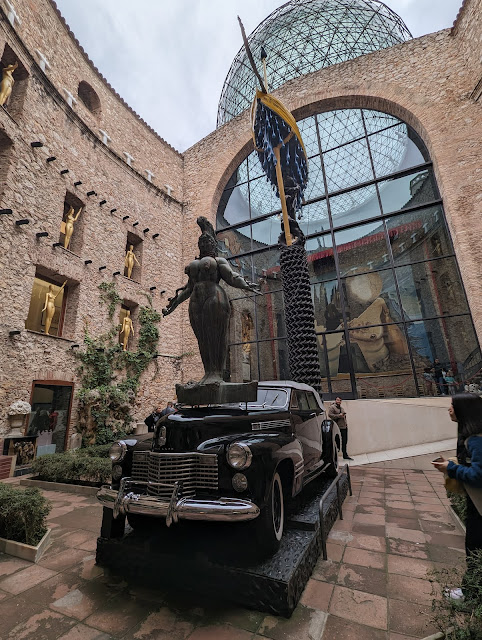

Sometimes traveling to another city can transport you to another time. A couple of works in Bilbao on the Bay of Biscay remind us how different the world was only a third of a century ago. When construction began on Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Bilbao Museum in 1991, democracy seemed to be expanding. An attempted authoritarian Kremlin coup failed that year, and the Berlin Wall had fallen 2 years before. Midway through the the construction of the Guggenheim's free-form titanium curves, in May of 1994, the apartheid regime in South Africa gave way to the country's first democratically-elected president, Nelson Mandela.

Gehry's exuberant design expressed the optimism of the era, seeming to imply a future of limitless possibility. The vast amount spent on the building during its six years under construction seemed a kind of bet placed on a future of prosperity and peace, in which people would travel to see an art museum that was itself a work of art.

Not far away, Santiago Calatrava's daring design for the Zubizuri Footbridge was completed in May 1997, a few months before the opening ceremony at the Bilbao Guggenheim. The 75 meter span of the glass-tiled walking surface over the Nervion river, suspended from a tilted steel arch by a curtain of cables, formed a link between the Uribitarte left bank and a popular pedestrian area on the Campo de Volantin right bank. The name Zubizuri means "white bridge" in the Basque language, and like Gehry's Guggenheim, Calatrava's bridge instantly became a landmark and a symbol of the city.

Over time the glass tiles of the walking surface, never especially practical in a rainy climate, have been covered with a non-slip surface, but the graceful optimism of the Calatrava bridge, as some fans now call it, seems to land like a cheerful alien spacecraft in a world haunted by the fires and floods of climate change, and by seemingly endless wars...

Around 24 hours of road travel in the northeasterly direction from Bilbao will land you in Malmo, Sweden, where you will find a 54-story apartment building, also designed by Santiago Calatrava, called the Turning Torso, completed in 2005...

The building can trace its origins to the shipbuilding past of Malmo, and to a marble sculpture Calatrava based on a twisting human form. The head of the HSB housing cooperative was intrigued by the sculpture, and familiar with Calatrava's bridge designs. Meeting with Calatrava led to a exploration of the "turning torso" concept.

Up until 2002, the. tallest element in Malmo was a shipbuilding crane called the Kockum Crane. Upon its demolition, city planners were looking for a tall element that would serve as a landmark and also as a link to that blue-collar, shipbuilding past. Calatrava's Turning Torso, with its 9 vertical segments of rotating pentagonal solids and its external steel framework, serves that symbolic function...

The top segment of Turning Torso is turned 90 degrees in a clockwise direction from the bottom segment. The bottom two segments serve as office space, while the top seven segments provide 147 apartments. The building won a Gold Emporis Skyscraper award in 2005, and in 2015 it won the 10 Year Award from the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Like the Guggenheim Bilbao and the Zubizuri Bridge, it seems today a visitor from a happier time, when architecture, engineering and sculpture met in a zone beyond categories or labels, but with plenty of funding for construction...

*Photo Credits:

All photos were graciously provided by Veronika Sprinkel, who has become our unofficial, and so far unpaid, European correspondent.

*Footnotes:

The Guggenheim Bilbao was previously featured in our post from June 9, 2019, entitled "Roadside Attraction: Guggenheim Bilbao—Sketches of Spain Part 1".

.jpg)