Henry Ford once said that he tipped his hat whenever an Alfa Romeo drove by. He might have been thinking of something like the 6C-1750 Flying Star shown below, bodied by Carrozzeria Touring in Milan, a home town the coachbuilder shared with Alfa. In January of 1931, Felice Bianchi Anderloni had his draftsman Seregni sketch the Flying Star idea for a big Isotta Fraschini*. But when Josette Pozzi ordered an Alfa 6C-1750 Gran Sport roadster that same year, she had Anderloni and his team cook up something similar for her. Like the Isotta, the little Alfa features the distinctive chrome spear dipping down at the rear of the cut-down doors. Hood vents follow the same downward curve. Unlike the Isotta, the Alfa's rear fender sweeps over the trailing edge of the front one, forming a streamlined biplane step instead of a running board...

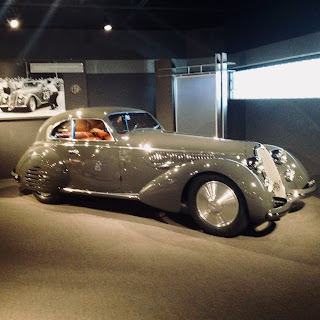

By the end of the Thirties, Anderloni had moved beyond streamlined effects into real aerodynamics. Like Zagato*, Touring attracted clients who wanted light weight and high performance. They developed a system of light alloy panels formed around a tubular steel framework, called Superleggera ("superlight"). The 6C 2300MM shown below features ovoid headlight lenses sloping with the rounded fenders, and side windows that are curved in plan as well as section...

The fastback roof form is teardrop-shaped in plan as well as section. Note the seamless integration of rear fender forms with the roof, and the way the designers avoided straight lines even in the spare tire lid. Rear lighting is not much more than you'd find on a motorcycle.

Touring took on the dream assignment of the era, bodying many of the 41 Alfa 8C 2900 series that were alleged to have been built to use up leftover Grand Prix racing engines. Nobody ever explained how Alfa wound up with so many unused engines from their racing program. It didn't matter; the car's reputation as the fastest road car of the time, along with sleek teardrop shapes from Touring as well has Pinin Farina, meant Alfa sold every specimen they could build.

Touring also bodied berlinettas on the 8C 2900B chassis. The Collier Collection at the Revs Institute has a long-chassis model from 1938. Note the slotted rear fender skirts, a variation on those on the red car shown above.

A "Lungo" 8C 2900B coupe displayed outside the LeMay Museum in Seattle displays the same tapered, restrained curves...and the same restrained lighting.

Any 8C 2900 Alfa was a special car even without the Touring bodywork. Here's the 220 hp inline eight with twin overhead cams, with two four-cylinder blocks separated by the drive for the supercharger...

In the April of 1939, Touring built this 6C 2500SS coupe to participate in that year's Le Mans with a fully integrated envelope body and no separation between front and rear fenders. The car dropped out of the race with mechanical troubles, but its design forecast the streamlined coupes and spiders that Touring built for BMW beginning the next month...

The rounded, tapered tail presages the racers that would appear at Le Mans after the war. The rounded envelope form would appear on Aston Martins, Porsches, and Ferraris.

In the early post-WW2 era Alfa abandoned the eight cylinder cars, and concentrated on their 6C2500 while preparing their 1900 four-cylinder line for the mass market. The 1949 Villa d'Este was notable for the way that the sweeping flanges formed over the wheel openings enliven the flanks (and strengthen the alloy panels) without applied brightwork. Note the way the curve of the rear fender flows into the door panel, again avoiding the massive look of the early slab-sided envelope-bodied racers. This car is also distinguished by an usually glassy greenhouse for the 1940s...

In the same year, Touring began to body Ferraris using the same Superleggera method. The car below is unusual for a very early Ferrari in that it's not a racer. The 166 two-liter V12 notchback coupe is built on the same short wheelbase as the famous Touring barchetta racers, but is so focused on road duty that it wears hubcaps, something that disappeared from Ferraris very soon after...

Touring was master at forming alloy into smooth, seamless contours, and the tapered rear end of this 166 demonstrates that. The narrow teardrop tail lights also appeared on 166 barchetta Touring built for Gianni Agnelli, the Fiat mogul...

Also in 1949, Touring created the 166 LM berlinettas for racing duty at Le Mans and in the Mille Miglia. Here the roof takes on a fastback form. Note that on the 166 LM below and the coupe above, the flange formed into the flanks connects the wheel openings, unlike on the Alfa Ville d'Este...

It was Anderloni's work on the Ferrari 166 barchetta, however, that made Ferrari famous. It helped that Luigi Chinetti* won Le Mans in a 166 barchetta in 1949. But Anderloni, aided by Federico Formenti, achieved an economy of line and fitness of form to purpose that rarely came together so well...

The eggcrate grille became a Ferrari trademark, and the deft way the concave trough between the fender peak and the hood wraps around the headlights inspired later designs, like the AC Ace. Barchetta means "little boat". And what Touring delivered to Chinetti for Ferrari's racing effort was tidy and shipshape in every way...

Note that the flange formed above the wheel openings curves upward around the rear wheel, and that the rear fender line is not straight as on the coupes. The effect is to visually lower the car, so that you don't notice the short (88 inch) wheelbase as you do on the red coupe.

The barchetta was so successful that Touring applied it to the 195, 212 and 340 as Ferrari introduced bigger engines to meet the demands of racers, especially in America. Touring built one 212 long-wheelbase barchetta for Henry Ford II, and a more compact 212 for John Edgar, shown below. The curved indent wraps around the tail lights as well as the headlights on these late (1952) barchettas, and the Edgar car has a smiley bright metal grille frame, an unusual appearance of decoration on a barchetta...

Touring's work on Alfa and Ferrari caught the attention of Wilfredo Ricart,the engineer running Spain's Pegaso truck factory as it tried to launch a line of exclusive sports cars to create more interest in the trucks. Early Pegasos had dumpy bodywork hiding their interesting transaxle chassis and 4-cam V8. Anderloni and Formenti managed to work their magic on a prototype Z-102 berlinetta in 1952. Note the way the C-pillar is made to seem thinner by the circular ornament that links side and rear windows. The cutouts in the fastback deck provide a place for lighting, and echo nostrils cut into the hood on production coupes, of which there were around 3 dozen...

Touring also bodied a small number of competition coupes like the '54 Panamericana shown below. These lost the nostrils in the hood, got bigger grilles with the trademark Pegaso crossbars, plexiglas covers over the headlights, and sliding side windows. As with the Ferrari 166, designers Anderloni and Formenti managed to distract from the short wheelbase. Unfortunately, they couldn't do anything about the heavy steering or the cooling system problems...

Touring also built come competition spiders in similar style in 1953 and '54, and the car shown below was equipped with a supercharger. These cars were not successful in endurance racing, partly because of lack of development effort by the factory. They were pretty, though...

While Touring built half of Pegaso's bodies, that only meant 42 cars. They did much better with a series of 1900-based Sprint Coupes starting in 1951, and were able to build about 20 times as many of these cars, culminating in the completely restyled Super Sprint released late in 1955. Careful proportions and contours manage to achieve a timeless fitness of form.

A detail shared with the white Pegaso spider above is found at the trailing edge of the front wheel arch; it's curved in section, showing how the alloy panels are formed around metal tubes. Lighting at the rear is generous compared with Touring's Thirties Alfas...

In the world of production cars, success can breed success. When Maserati decided to finally make a real production car, they invited proposals from Allemano, Touring and Vignale. Touring got to build the 3500GT coupes beginning in 1957, and Vignale the spiders. But the contract for those coupes was the plum, as it led to Touring producing 1,981 of the deftly-detailed alloy coupe shown below. By contrast, Vignale built only 242 spiders. All featured the new twin-plug aluminum block twin-cam six. A landmark car, and not just for Maserati...

When Lancia introduced their new Flaminia the next year, Pinin Farina styled the sedans, and Touring got the contract for the GT coupes and convertibles. The design followed the proportions of Touring's Maserati, but surfaces were more sheer and devoid of details like the chrome fender peaks and vents give the 3500GT a human touch. The Flaminia body is a bit like one of those steel and glass buildings from this period; on the outside, you keep trying to find some detail that makes you feel at home...

The oddly peaked front fenders and quad headlights didn't do it for me, though I loved the 3 Weber carbs under the hood of my old 3C, as well as the insignia...

The interior was that place you felt at home. Just sitting inside made you feel rich...

At the rear, the tail lights seemed positively over-scaled compared to the Super Sprint or the Maserati. In connecting the front to the rear, though, my much-loved old car seemed to need a bit more work from the designers. Anderloni's team showed a more confident hand when they drew their next big assignment, the Aston Martin DB4, which appeared right after the Lancia. Gone were the unresolved headlights and quirky taillights, and the sharp peaks on the Lancia's fenders. These were replaced with smoothly rounded front fenders, a glassy fastback greenhouse, and sheer flanks relieved of the slab-sided look with functional fender vents. The new car was shown late in 1958, and when production got moving in 1959 it was able to exploit Aston's victory in that year's Le Mans. This is an early Series 1 car, with the frameless door glass and elongated tail lights that Touring specified. The DB4 would never look better...

Aston would show up again on Touring Superleggera's client list, along with Jensen and Lamborghini. This is Part 1 of a two-part survey of Touring's work. Stay tuned for subsequent developments...

*Footnote: The Isotta Fraschini Flying Star is pictured along with the Touring-bodied 8C in "Forgotten Classic: Isotta Fraschini", in our Archives for Sept. 4, 2016. Zagato-bodied Alfas are the subject of "Body by Zagato Part 2: Five Decades of Alfa Romeos", posted May 6, 2020. Other early Ferraris like the 166 appear in "Lost Roadside Attraction: Luigi Chinetti Motors", posted May 6, 2018. We spent more time with Pegasos, bodied by Touring, Saoutchik and Serra, in "Forgotten Classic: Pegaso, Spain's Flying Horse", posted June 21, 2019.

Color Photo Credits:

All color photos are by the author.

All color photos are by the author.

Monochrome Photo Credits:

Alfa Romeo Flying Star, Pegaso Z-102 Prototype: Touring Superleggera

Alfa Romeo Ville d'Este: Alfa Romeo S.p.A.

Alfa Romeo Flying Star, Pegaso Z-102 Prototype: Touring Superleggera

Alfa Romeo Ville d'Este: Alfa Romeo S.p.A.

Ferrari 212 Barchetta & Pegaso Panamericana: en.wheelsage.org

Maserati 3500GT: Officine Alfieri Maserati S.p.A.

Lancia interior: Car & Driver archives

Lancia interior: Car & Driver archives

Aston Martin DB4: Aston Martin Lagonda