In "You Can't Catch Me", an early rock & roll road trip from Chuck Berry, he tells us about his new Airmobile with "powerful motor and hideaway wings." When the highway patrol gives chase, Berry hits a button and those hideaway wings help him fly away. By 1956, when Berry wrote the song, this idea had already been a staple theme on covers of science (and science fiction) magazines for well over twenty years...

After World War II, the increasing role of technology and a mood of expansive optimism encouraged Americans to think that flying cars were just around the corner. In illustrator and satirist Bruce McCall's vision of this era's often zany trust in the trappings (and contraptions) of the early Jet Age, a hapless Henry J, the ill-fated compact car from Henry J. Kaiser's car company, is about to be launched over an unsuspecting neighborhood by something that looks suspiciously like the catapult on an aircraft carrier...

Argentinian illustrator Alejandro Burdisio has a vision of yesterday's futurism that is no less infused with humor than McCall's, but his images seem to show a later moment in that future. Rather than depict tidy suburban streets rendered with National Geographic colors, Burdisio shows us congested, smoggy cities whose skies are clogged with ordinary cars and trucks that just happen to fly. He has a feel for the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne architecture of that period, with its possibly naive faith in the Machine Age, that rivals the faithfulness of detail shown in McCall's pioneering book of retro-futurism, Zany Afternoons...

The artist who produced the ad below seems to have never entertained any of McCall's qualms about safety, or Burdisio's questions about air traffic control for all that airborne rolling stock. Instead, the artist presents a safe, clean world of personal flying saucers recharged by power from America's electric power industry. The family dog is a cheery touch, as is the midcentury modern house with its own saucer waiting in the driveway below...

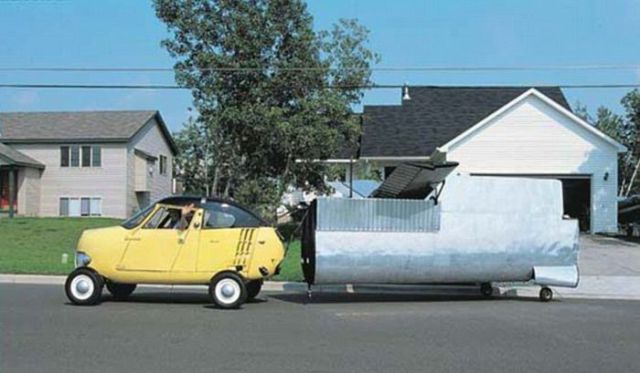

Starting in 1949, an inventor named Moulton Taylor actually attempted to make the flying car a reality, and progressed to the point of building prototypes that actually flew. A Lycoming engine drove a pusher propeller of Taylor's Aerocar in flight, and the front wheels when operating on the road...

Taylor configured folding wings that were towed behind the Aerocar on the road, and the transition from car to aircraft was alleged to take no more than five minutes. The Aerocar's light weight (1,500 lb. empty, 2,100 lb. gross) made for a maximum 110 mph air speed, while road-going travel was limited to 60 mph. Perhaps the tall stance and small wheels would have discouraged sudden directional changes on the ground...

Four Type I Aerocars were built from 1949 to 1960. A non-roadable Aerocar II was built in 1966. One of the flying Aerocars was sold to television actor Bob Cummings, and it appeared in his TV series. Moulton Taylor attempted to get financing for series production of the Aerocar through aerospace firm LTV Corporation, and this would have required a minimum order of 500 units. As Taylor was only able to attract about 250 prospective buyers, production ended after the Aerocar III prototype...

That single Aerocar III is now on view at Seattle's Museum of Flight. The body design is tilted more towards "flyable car" than "roadable plane". The outrigger wheels of Aerocar I have been tucked under a compact, rounded envelope body that looks, especially at the front, for all the world like a chubby Jaguar E-Type. This is perhaps a reminder that by the time the Aerocar adventure ended, rising costs of private aviation meant that people who could afford planes could also afford to leave them at the airport, and drive home in a Jaguar or Porsche.

*Footnote: For our series on jet-themed cars and cars powered by actual jet turbines, you could begin with "Jet Cars, Real & Not So Real" from 5/21/16, have a look at "Jet Cars Part 2: Chrysler Turbine Car" from 5/21/16, and finish with "Jet Cars Part 3: Chrysler Turbine Epilogue" from 5/25/16. For some notes on jet styling themes, there's "Jets vs. Sharks: Pinin Farina Cadillacs" from 5/15/16.

Bibliography and sources: Bruce McCall's Zany Afternoons, published in 1982 by Knopf, is a foundational work of futurist nostalgia, and is recommended for anyone even marginally interested in the Machine Age, or in the past, or even in afternoons. Alejandro Burdisio's digital illustrations are on view at facebook.com/alejandroburdisio and at illusion.scene360.com.

Photo Credits:

Top: Illustrated World Magazine, reproduced on pinterest.uk

2nd: Bruce McCall, reproduced on TED.com

3rd: Alejandro Burdisio, reproduced on crossconnect.com

4th: America's Independent Electric Light and Power Companies

5th: pinterest.uk

6th: atomictoasters.com

Bottom: wikimedia

No comments:

Post a Comment